What Are Black Holes?

Black holes are regions of spacetime where gravity is so strong that nothing—not even light or other electromagnetic waves—can escape once past the event horizon. They are among the most fascinating and mysterious objects in the universe, predicted by Einstein's theory of general relativity and now observed through gravitational wave detection.

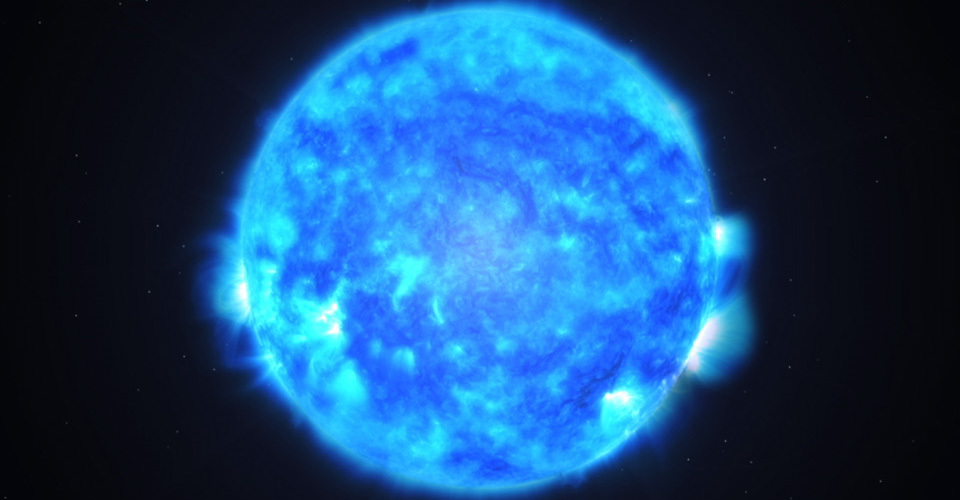

Massive Stars

The story of stellar mass black holes begins with massive stars—stellar giants that are at least 8 times more massive than our Sun, with the most extreme being 100+ solar masses. These cosmic powerhouses burn through their nuclear fuel at prodigious rates, living fast and dying young compared to smaller stars.

In their cores, massive stars fuse hydrogen into helium, then helium into carbon, and progressively heavier elements in an "onion-layer" structure. This process continues until iron accumulates in the core—iron fusion absorbs energy rather than releasing it, setting the stage for catastrophic collapse.

Key Characteristics

- Mass range: 8 to 100+ solar masses

- Lifespan: Only millions of years (vs. billions for Sun-like stars)

- Luminosity: Up to millions of times brighter than the Sun

- Core fusion: Produces elements up to iron through nuclear burning

- Fate: Supernova explosion → neutron star or black hole

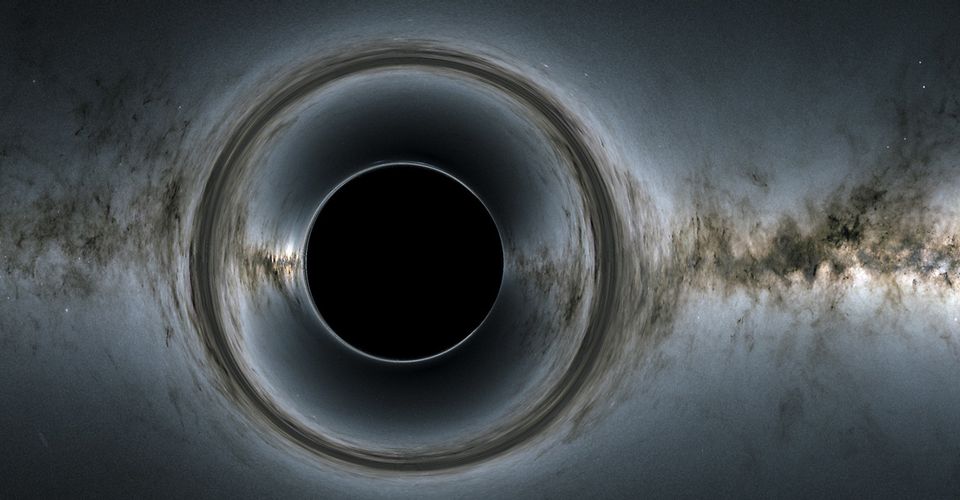

Stellar Mass Black Holes

Stellar mass black holes form when massive stars (typically more than 20 times the mass of our Sun) reach the end of their lives. When such a star exhausts its nuclear fuel, it can no longer support itself against its own gravity and collapses. If the remaining core is massive enough (roughly 3 solar masses or more), nothing can halt the collapse, and a black hole forms.

Key Facts

- Mass range: 5 to ~100 solar masses

- Formed from the death of massive stars

- Event horizon radius scales with mass

- Cannot be directly observed—detected by their effects

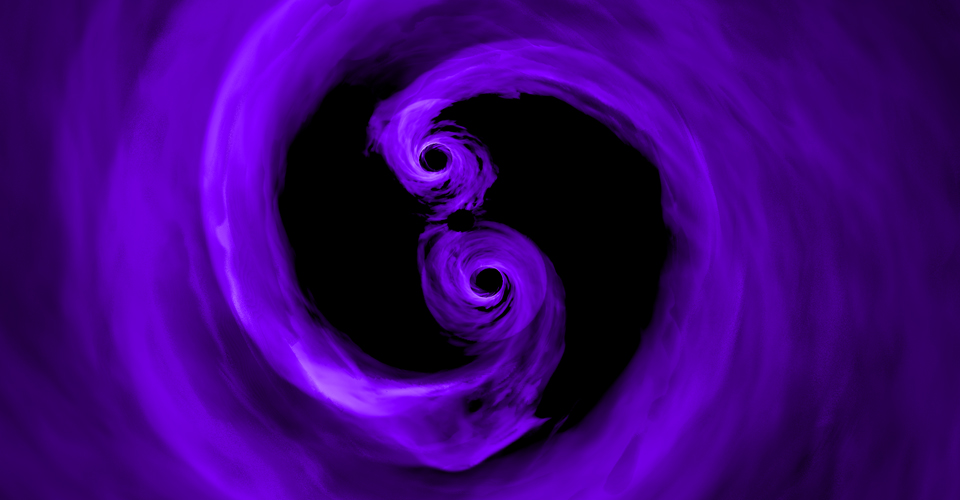

Binary Black Hole Systems

A binary black hole is a system consisting of two black holes orbiting around their common centre of mass. These systems can form in two main ways: from the evolution of binary star systems where both stars become black holes, or through dynamical capture in dense stellar environments like globular clusters.

As binary black holes orbit each other, they gradually lose energy by emitting gravitational waves. This causes their orbit to shrink over time, bringing them closer together in an ever-tightening spiral that eventually leads to merger.

Formation Channels

- Isolated binary evolution: Two massive stars evolving together

- Dynamical formation: Black holes pairing up in dense star clusters

- Hierarchical mergers: Products of previous mergers finding new partners

Black Hole Mergers

When two black holes spiral close enough together, they merge in a violent event that briefly releases more power than all the stars in the observable universe combined. The merger process occurs in three distinct phases.

Merger Phases

- Inspiral: Black holes orbit each other, gradually getting closer as they emit gravitational waves

- Merger: The black holes combine into a single, highly distorted black hole

- Ringdown: The merged black hole settles into a stable state, emitting final gravitational waves

The final black hole has less mass than the sum of the original two—the "missing" mass (typically 5-10% of the total) is radiated away as gravitational wave energy.

Gravitational Waves

Gravitational waves are ripples in the fabric of spacetime caused by the acceleration of massive objects. Predicted by Einstein in 1916, they were first directly detected on September 14, 2015, by the LIGO detectors—from a binary black hole merger about 1.3 billion light-years away.

These waves travel at the speed of light and carry information about their origins, as well as valuable clues about the nature of gravity itself. Unlike electromagnetic radiation, gravitational waves pass through matter almost unimpeded, allowing us to observe events that would be invisible to traditional telescopes.

Detection & Observatories

- LIGO (USA): Two detectors in Washington and Louisiana

- Virgo (Italy): European detector near Pisa

- KAGRA (Japan): Underground detector using cryogenic mirrors

- Future LISA (Space): Planned space-based detector for lower frequencies

Why This Matters

The study of black holes and gravitational waves opens new windows to the universe. It helps us understand stellar evolution, test general relativity in extreme conditions, and explore the fundamental nature of spacetime. This is an exciting time for astrophysics, with each new detection revealing more about these cosmic giants.